9

19

29

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

49

How can the Pentagon’s energy transition mineral stockpiles be repurposed toward the green transition?

4 Dec 2025

4 December 2025

•

-

1.

Oli Brown, Sebastian Dunnett, Elizabeth Steyn and Claudia S. De Windt, “Critical Transitions: Circularity, equity, and responsibility in the quest for energy transition minerals”, United Nations Environment Programme, 18 November 2024, available here; Daniele La Porta Arrobas, John Richard Drexhage, Thao Phuong Fabregas Masllovet and Kirsten Lori Hund, “Minerals for Climate Action: The Mineral Intensity of the Clean Energy Transition”, World Bank Group, 25 May 2023, available here; John R. Owen, Deanna Kemp, Alex M. Lechner, Jill Harris, Ruilian Zhang and Éléonore Lèbre, “Energy transition minerals and their intersection with land-connected peoples”, Nature Sustainability, 2023, volume 6, pp. 203–211.

-

2.

Vlado Vivod, Ron Matthews and Jensine Andresen, “Securing defense critical minerals: Challenges and U.S. strategic responses in an evolving geopolitical landscape”, Comparative Strategy, 2025, Volume 44; Mark Griffiths and Kali Rubaii, “Late modern war and the geos: The ecological ‘beforemaths’ of advanced military technologies”, Security Dialogue, 2025, Volume 56, pp. 38-57; Benedetta Girardi, Irina Patrahau, Giovanni Cisco and Michel Rademaker, “Strategic raw materials for defence: Mapping European industry needs”, Hague Centre for Strategic Studies, 2023, available here.

-

3.

See: U.S. Geological Survey, “What is a critical mineral?”, U.S. Department of the Interior, 30 September 2025, available here.

-

4.

Adrienne Buller and Thea Riofrancos, “Where Capital and Nature Meet,” The Breakdown, 22 September 2025, available here; Cleodie Rickard and Laura Bannister, “Material realities: Who needs ‘critical minerals’ and at whose expense?”, Global Justice Now, 6 August 2025, available here; Ian Morse, “Communicating the Energy Transition: A Literature Review of Public Discourse and Narratives About Energy Transition Materials”, Harmony Labs, June 2025, available here

- 5.

-

6.

Thea Riofrancos, “The ‘critical minerals’ rush could result in a resource war”, Financial Times, 12 March 2025, available here; Emily Iona Stewart, “Material realities: Who needs ‘critical minerals’ and at whose expense?”, Global Witness, 20 March 2025, available here; Jiayi Zhou and André Månberger, “Critical Minerals and Great Power Competition: An Overview”, SIPRI, October 2024, available here.

-

7.

Patrick Bigger, Nick Pearce, Khem Rogaly, and Ketaki Zodgekar, “Less War, Less Warming: A Reparative Approach to US and UK Military Ecological Damages”, Common Wealth and Climate and Community Institute, 2023, available here.

-

8.

Isabel Estevez and Thea Riofrancos, “Global Green Industrial Policy”, Climate and Community Institute, 2025, available here

-

9.

Xiao Liang, Nan Tian, Dr Diego Lopes da Silva, Lorenzo Scarazzato, Zubaida A. Karim, Jade Guiberteau Ricard, “Trends in World Military Expenditure”, SIPRI, April 2025, available here.

-

10.

Rodrigo Carril and Mark Duggan, “The impact of industry consolidation on government procurement: Evidence from Department of Defense contracting”, Journal of Public Economics, 2020, Vol 184; William D. Hartung and Stephen Semler, “Profits of War: Top Beneficiaries of Pentagon Spending, 2020 – 2024, Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft and Costs of War at Brown University’s Watson School of International and Public Affairs, 2025, available here

-

11.

Zaynab Quadri, “Anatomy of a Defense Budget”, Phenomenal World, 27 March 2025, available here.

-

12.

Mariana Mazzucato, The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths, Anthem Press: 2013, pp 95-107.

-

13.

The Defense Production Act is a US law which empowers the President with a broad set of authorities to influence domestic industry in the interest of national defense, see: Alexandra G. Neenan, “The Defense Production Act of 1950: History, Authorities, and Considerations for Congress”, Congressional Research Service, 6 October 2023, available here.

-

14.

Both the Trump and Biden administrations invoked the DPA to fund critical mineral supply chains. The Biden administration’s earlier DPA actions in 2022 focused on expanding domestic sourcing by providing the Pentagon with more administrative leverage to approve mineral project funding.

-

15.

Cristian Barrios, “Issue Brief: Growing U.S. Public Financing For Minerals Projects”, Friends of the Earth, available here.

-

16.

Hannah Northey, “Inside Trump’s foray into mineral ownership”, E & E News by Politico, 8 October 2025, available here.

- 17.

- 18.

-

19.

The National Defense Stockpile was first established in 1939 to retain stocks of strategic and critical materials to “serve the interest of national defense only,” defining strategic and critical materials as those that “(A) would be needed to supply the military, industrial, and essential civilian needs of the United States during a national emergency, and (B) are not found or produced in the United States in sufficient quantities to meet such need,” see: “Strategic and Critical Materials Stock Piling Act”, U.S. Government Publishing Office, 23 January 2024, available here.

-

20.

The concept of critical and strategic minerals can be traced back to at least the first World War, when many of the involved nations began to experience shortages of materials essential to sustaining the war effort and began to institutionalise efforts to secure supplies. In the United States, the Army and Navy Munitions Board was established in the US Department of War in 1922 to acquire and stockpile materials, Anton R. Chakhmouradian, Martin P. Smith and Jindrich Kynicky, “From “strategic” tungsten to “green” neodymium: A century of critical metals at a glance,” Ore Geology Reviews, 2015, Volume 64, Pages 455-458; see also: Megan Black, The Global Interior: Mineral Frontiers and American Power, “(Harvard University Press: 2018, 68–83. For additional analysis on the historic dynamics of military mobilisations and the emergence of critical minerals, see: Philip Johnstone and Anabel Marin, “Beyond the twin transition: military drivers of critical minerals’ expansion”, Institute of Development Studies (IDS), forthcoming.

-

21.

Daniel F. Runde and Austin Hardman, “Elevating the Role of Critical Minerals for Development and Security”, Center for Strategic & International Studies, 2023, available here; Marc Humphries, “Critical Minerals and U.S. Public Policy”, Congressional Research Service, 28 June 2019, available here; Vivian Chime, “Trump follows the minerals trail — but for weapons, not clean energy”, Climate Change News, 4 April 2025, available here; “Strategic and Critical Materials Stock Piling Act”, International Energy Agency, 31 October 2022, available here.

-

22.

U.S. Government Accountability Office, “Rare Earth Materials: Developing a Comprehensive Approach Could Help DOD Better Manage National Security Risks in the Supply Chain”, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 11 February 2016, available here; U.S. Department of Defense, Office of Inspector General, “Procedures to Ensure Sufficient Rare Earth Elements for the Defense Industrial Base Need Improvement”, U.S. Department of Defense, 3 July 2014, available here; Camilla Hodgson, Steff Chávez and Aime Williams, “Pentagon steps up stockpiling of critical minerals with $1bn buying spree”, Financial Times, 11 October 2025, available here; Jack Farchy, Joe Deaux, and Annie Lee, “US Seeks $500 Million Cobalt Stash, First Buy Since Cold War”, Bloomberg, 21 August 2025, available here.

-

23.

Office of International Affairs, “U.S. Departments of Energy, State and Defense to Launch Effort to Enhance National Defense Stockpile with Critical Minerals for Clean Energy Technologies”, U,S, Department of Energy, 25 February 2022, available here; Reed Blakemore, Alexis Harmon and Peter Engelke, “Critical minerals in crisis: Stress testing US supply chains against shocks”, Atlantic Council, 9 October 2025, available here.

-

24.

See: Cameron M. Keys, “Emergency Access to Strategic and Critical Materials: The National Defense Stockpile,” Congressional Research Service, 14 November 2023, available here; “Strategic and Critical Materials Stock Piling Act (Amended through FY 2024)”, Defense Logistics Agency, 2024, available here; In the press release announcing the MOA, for example, Deputy Secretary of Defense Kathleen Hicks frames the energy storage in “creating new advantages for our warfighters,” see: Office of International Affairs, “U.S. Departments of Energy, State and Defense to Launch Effort to Enhance National Defense Stockpile with Critical Minerals for Clean Energy Technologies“, U,S, Department of Energy, available here.

-

25.

“Energy Transition Materials Narrative Landscape: Across news, industry, and policy information domains in Canada, Chile, DRC, Germany, Indonesia, Mexico, Peru, Portugal, USA, Findings Summary”, Harmony Labs, August 2025, available here.

-

26.

Dr. Tom Moerenhout, Lilly Yejin Lee, and Dr. James Glynn, “Critical Mineral Supply Constraints and Their Impact on Energy System Models”, Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia, 12 June 2023, available here; IEA, “Overview of outlook for key minerals – Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2025”, IEA, 2025, available here; Justin Alger, Jessica F. Green, Kate J. Neville, Susan Park, Stacy D. VanDeveer, and D. G. Webster, “The false promise of deep‑sea mining”, NPJ Ocean Sustainability, 2025, volume 4.

-

27.

John R. Owen, Deanna Kemp, Jill Harris, Alex M. Lechner and Éléonore Lèbre, “Fast track to failure? Energy transition minerals and the future of consultation and consent,” Energy Research & Social Science, 2022, Volume 89; Arnim Scheidel, Daniela Del Bene, Juan Liu, Grettel Navas, Sara Mingorría, Federico Demaria, Sofía Avila, et al., “Environmental conflicts and defenders: A global overview,” Global Environmental Change, 2020, Volume 63.

-

28.

Daan Van Brusselen, Tony Kayembe-Kitenge, Sébastien Mbuyi-Musanzayi, Toni Lubala Kasole, Leon Kabamba Ngombe, Paul Musa Obadia, Daniel Kyanika Wa Mukoma, et al., “Metal mining and birth defects: a case-control study in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo,” Lancet Planet Health, 2020, Volume 4.

-

29.

Michael J. Lawrence, Holly L.J. Stemberger, Aaron J. Zolderdo, Daniel P. Struthers and Steven J. Cooke, “The effects of modern war and military activities on biodiversity and the environment”, Environmental Reviews, 2015, volume 23; Griffiths and Rubaii, “Late modern war and the geos: The ecological ‘beforemaths’ of advanced military technologies”, Security Dialogue, pp 38-57; Reuben Larbi, Kali Rubaii, Benjamin Neimark and Kirsti Ashworth, “Parting the Fog of War: Assessing Military Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Below”, The Extractive Industries and Society, 2025, Vol. 23; Amira Aker, John Doe, Jane Smith, Michael Brown, Lisa Taylor, Robert Johnson, Emily Davis, et al., “The Ongoing Environmental Destruction and Degradation of Gaza: The Resulting Public Health Crisis”, American Journal of Public Health, 2025, Vol. 115, pp. 1053–1061.

-

30.

“Energy Transition Materials Narrative Landscape: Across news, industry, and policy information domains in Canada, Chile, DRC, Germany, Indonesia, Mexico, Peru, Portugal, USA, Findings Summary”, Harmony Labs, available here.

-

31.

In terms of transparency, stockpiling materials through the DLA offers a higher level of public visibility and scrutiny than direct procurement by military contractors. Direct contractor purchases often have limited visibility, whereas materials procured by the DLA and subsequently distributed are likely to appear in public databases, providing more accessible information on these flows.

-

32.

Stew Magnuson, “Defense Logistics Agency Considers Dipping into Strategic Mineral Stockpiles,” National Defense, 20 June 2025, available here.

-

33.

Hodgson, Chávez and Williams, “Pentagon steps up stockpiling of critical minerals with $1bn buying spree”, Financial Times, available here.

-

34.

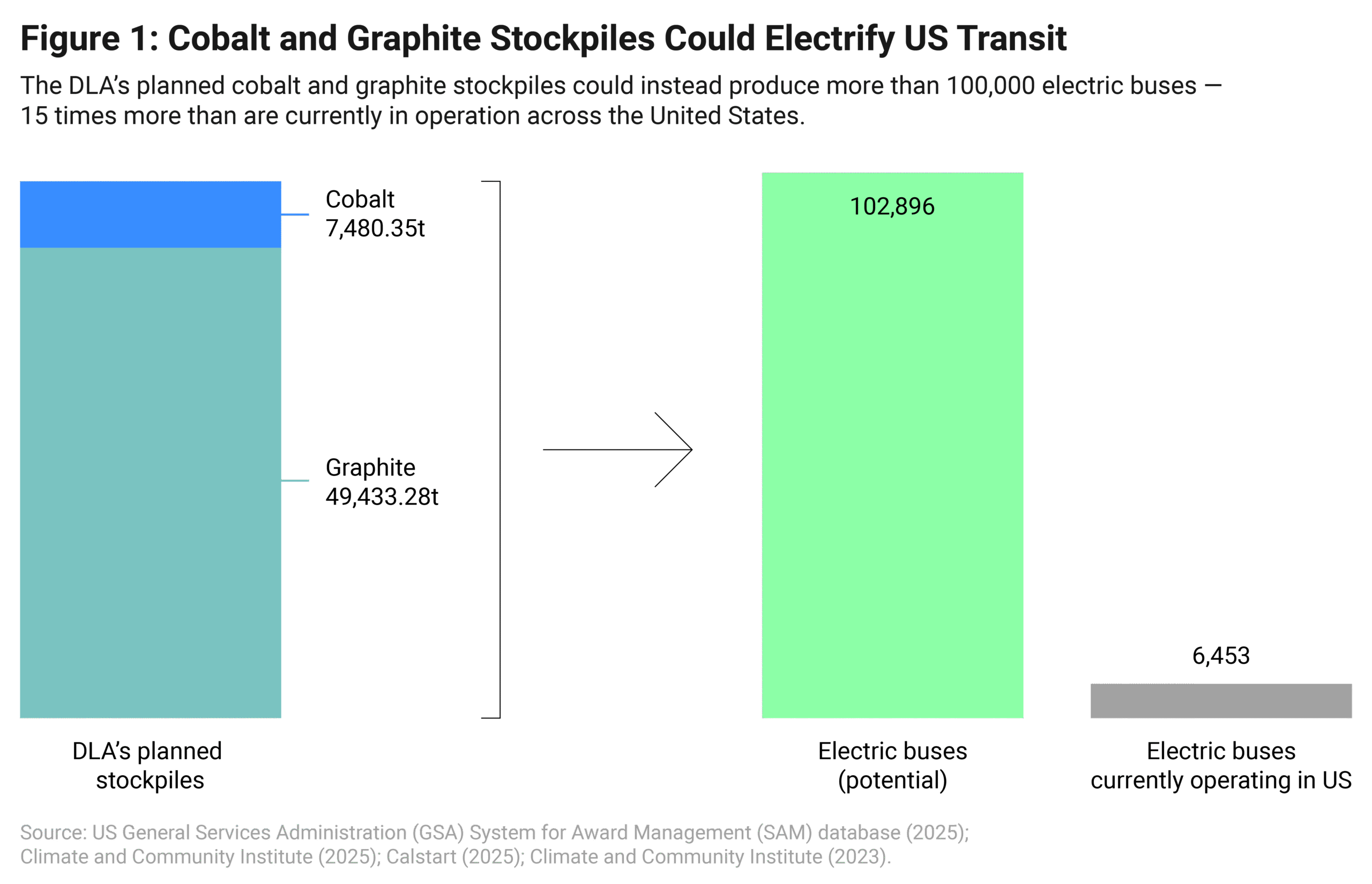

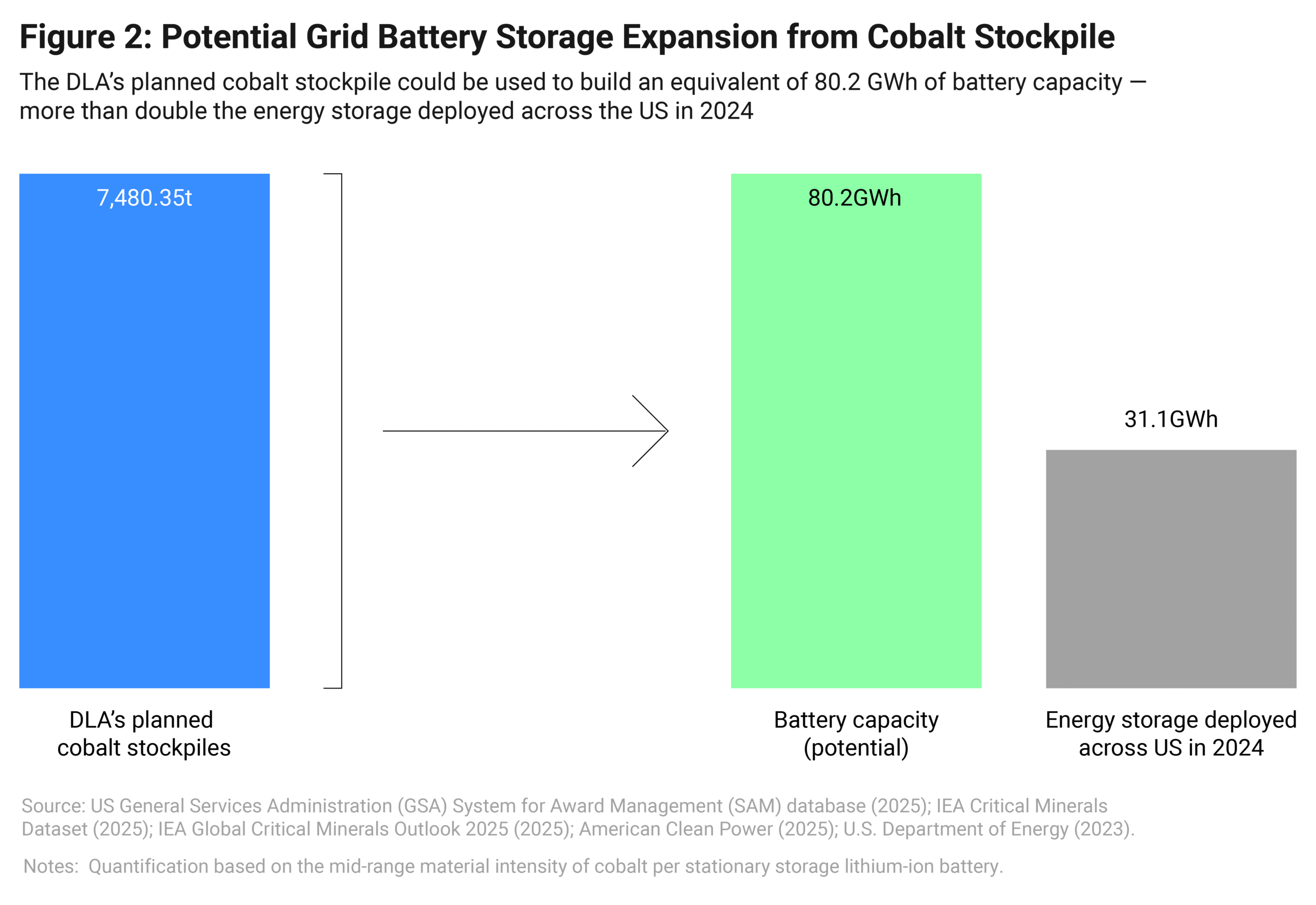

Material quantities are based on solicitations published in the U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) System for Award Management (SAM) database (sam.gov) between July 4, 2025, and November 7, 2025, “System for Award Management (SAM)”, U.S. General Services Administration, 2025, available here.

-

35.

“Strategic and Critical Materials Stock Piling Act”, International Energy Agency, available here.

-

36.

Tae-Yoon Kim, Eric Buisson, Amrita Dasgupta, Shobhan Dhir, Félix Gagnon, Alexandra Hegarty, Gyubin Hwang, et al., “Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2025”, International Energy Agency (IEA), 21 May 2025, available here.

-

37.

Lorah Steichen, Mekedas Belayneh, Matthew Haugen, Patrick Bigger and Lucy Block, “Redirecting Energy Transition Minerals from the Pentagon Fleet to the Public Good”, Climate and Community Institute, February 2025, available here; Thea Riofrancos, Alissa Kendall, Kristi K. Dayemo, Matthew Haugen, Kira McDonald, Batul Hassan and Margaret Slattery, “Achieving Zero Emissions with More Mobility and Less Mining”, Climate and Community Institute, January 2023, available here.

-

38.

Mike Hynes and Kaila Lemons, “Zeroing in on Zero-Emission Buses The U.S. Advanced Technology Transit Bus Index”, Calstart, March 2025, available here.

-

39.

“Mineral requirements for clean energy transitions”, IEA, 2021, available here.

-

40.

According to IEA’s Critical Minerals Dataset, 4060.92 metric tonnes of cobalt are used for global grid battery storage as of 2024. According to IEA’s Global Critical Minerals Outlook, the United States accounts for a quarter of global demand. According to the US Energy Storage Monitor report, there was 37.143 GWh energy storage deployed in the US in 2024. Quantification based on the mid-range material intensity of cobalt per stationary storage lithium-ion battery as published by the US Department of Energy Critical Materials Assessment. See: International Energy Agency, “Critical Minerals Dataset”, IEA May 2025, available here; Kim, Buisson, Dasgupta, Dhir, Gagnon, Hegarty, Hwang, et al., “Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2025”, International Energy Agency, available here; “REPORT: Energy Storage’s Meteoric Rise Breaks Another Record”, American Clean Power Association (ACP) and Wood Mackenzie, March 2025, available here; “Critical Materials Assessment”, U.S. Department of Energy, May 2023, available here.

-

41.

Bernd Christiansen, Anneke Denda and Sabine Christiansen, “Potential effects of deep seabed mining on pelagic and benthopelagic biota,” Marine Policy, 2020, Volume 114.

-

42.

Elizabeth Claire Alberts, “A sales-pitch pivot brings deep-sea mining closer to reality”, Mongabay, 31 July 2025, available here; Psyche 16, Antoine Gillod, Tom Cariou, Andrew Thaler, Arlo Hemphill, Jackie Dragon, John Hocevar, et al., “Deep Deception How The Deep Sea Mining Industry Is Manipulating Geopolitics To Profit From Ocean Destruction,” Greenpeace, 2025, available here.

-

43.

“Fact Sheet: President Donald J. Trump Unleashes America’s Offshore Critical Minerals and Resources”, The White House, 24 April 2025, available here.

-

44.

Justin Alger, Jessica F. Green, Kate J. Neville, Susan Park, Stacy D. Van Deveer and D. G. Webster, “The false promise of deep-sea mining,” npj Ocean Sustain, 2025, 4.

-

45.

Evan Halper and Jake Spring, “Trump moves to open seabed to mining, unnerving other nations,” Washington Post, 24 April 2025, available here. Psyche 16, et al., “Deep Deception How The Deep Sea Mining Industry Is Manipulating Geopolitics To Profit From Ocean Destruction,” Greenpeace, available here.

-

46.

Alberts, “A sales-pitch pivot brings deep-sea mining closer to reality,” Mongabay, available here.

-

47.

Tobita Chow, “Cold War on a Warming World”, Transition Security Project, available here.